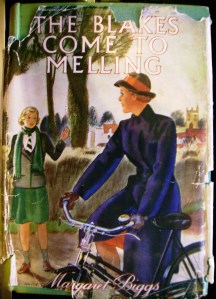

Enid Blyton’s Naughtiest Girl books are not Girls’ Own in the traditional sense, for the school includes boys as well as girls. Having said that, they fit many of the Girls’ Own traditions and tropes, and for such “simple” books (as they have often been called) are surprisingly interesting, as well as simply jolly good stories.

The majority of Girls’ Own schools are fairly similar to one another. They feature medium sized schools of between fifty and two hundred girls, run along traditional lines which are more or less still in use today. Misdemeanours are punished by lines, order marks or of course incarceration in the San. Rules are many, varied and unchangeable, not to mention frequently broken, and activities for each part of the day are carefully prescribed and controlled.

With the Naughtiest Girl books, though, Enid Blyton broke a mould which was later to be smashed to smithereens by Mabel Esther Allan. Whyteleafe is perhaps the only one of her three best-known schools which could have dealt with such a problem as naughty, spoiled, selfish Elizabeth Allen. The change in Elizabeth’s character is nicely dealt with and feels emotionally realistic, and some at least of the secondary and minor characters are appealing. But it’s the setting that really makes the Naughtiest Girl books so fascinating

The school is what is often described as “progressive”. The children make the rules, but they are also responsible for enforcing them as well as for sorting out other problems the children might have with one another or with school arrangements. This happens in weekly Meetings led by a Jury of Monitors and two Judges, William and Rita. The latter two are presented almost as God and Goddess in their own small realm (there are many Goddesses in Girls’ Own literature, and Rita is typical of them).

As previously mentioned, Whyteleafe School is also co-educational. This was almost certainly a practical measure on Enid Blyton’s part, since the stories were originally published in Sunny Stories, aimed at both boys and girls. Even so, it’s original for a school story of its time. Even more impressive is the fact that the school, while containing both boys and male masters, is run by two women, Miss Belle and Miss Best. Women and girls have equal power with men and boys, and often the balance of power in fact seems to lie with the females of the school – a hugely empowering message at a time when there was still great discrimination against women.

On the other side of the argument, one must wonder what parents and relations made of their children being made to give up all their money to be donated to a school pot and divided among the pupils. One can see the appeal of this socialism in action and the theoretical fairness of it, but surely it’s not realistic that either children or parents would not resent it.

It has been suggested that Whyteleafe was if not actually modelled on, then at least influenced by, A. S. Neill’s famous progressive school Summerhill. Summerhill, run almost entirely by the students, seems to have been enough of a success that it is still going in more or less the same form today. Whyteleafe is not so radical in its outlook – it seems unlikely that Miss Belle and Miss Best would have permitted the school to banish all rules (as happens periodically at Summerhill, only for them to be soon reinstated when chaos palls). Classes are compulsory at Whyteleafe, unlike Summerhill, although at times a higher level of tolerance of misbehaviour is shown than in many Girls’ Own books. For example, when on her first night Elizabeth claims she has a guinea-pig with a face like Miss Thomas’s she is neither “sat on” nor punished, though disapproval is shown by her classmates.

Of course there are some similarities with other more traditional Girls’ Own schools. Whyteleafe may be more tolerant in some ways, but its pupils do not hesitate to administer their rules as strictly as any other schools. Some of these, as in all fictional (and indeed real) schools, seem entirely unnecessary – such as that which states that no one except a monitor may have more than six items on her dressing table. This rules is so strictly enforced that three photographs of Elizabeth’s are confiscated on her first night, which seems rather harsh even as a result of the rudeness she exhibited on that occasion.

One of Whyteleafe’s greatest similarities to most Girls’ Own school is the way in which pupils’ better qualities are drawn out and lauded. This is something which many Girls’ Own schools claim to do, although Enid Blyton was particularly keen on it. Courage in particular is highly valued – a very Girls’ Own virtue. The delight of the entire school when Elizabeth bravely stands up and declares her intention of staying at school is huge and heartwarming, as it is when it is discovered in The Naughtiest Girl is a Monitor that it was she who rescued a small boy from drowning.

But while values may be similar in all schools and stories, that doesn’t stop Whyteleafe from being one of the most original and forward-looking schools in the entire Girls’ Own genre. Enid Blyton is often condemned for her traditional values and simple writing, yet simple writing frequently makes for a good rollicking story. As for traditional – Whyteleafe shows that she was entirely capable of breaking all the moulds she wanted to when she felt it appropriate. There is no doubt that Whyteleafe is, even today, a school with a difference.