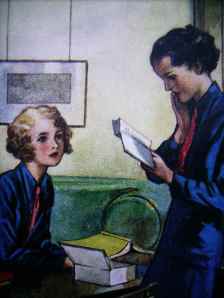

JP of the Fifth was written by Margaret Griffiths and published in 1937, during what might be called the heyday of the school story, and it is an excellent example of that genre. Like all the best school stories it is filled with adventure and excitement, appealing characters and almost no lessons. Published as a very satisfying fat hardback with thick pages, it is a handsome book to own and is beautifully illustrated by Terye Hamilton, whose sensitive drawings only add to the feeling of the book.

The story begins with the meeting of the two Joans (one of whom is conveniently called Pat) on the train to school. They switch identities so that Pat can fail a scholarship on Joan’s behalf (Joan being too intelligent to do so for herself) in order that Joan may go and live away from her hideous stepmother, and here begins all the confusion. The exchange turns out to be fortunate, for otherwise the plot against sweet, gentle Joan might have succeeded and she be defrauded of her rightful inheritance.

J.P. of the Fifth revolves around Pat, who is known as J.P. for her trademark judicial expression. It is Pat who suggests the change of identies, Pat who keeps Joan up to the mark throughout, Pat who suffers the greatest pain of guilt, Pat who is kidnapped (twice) in mistake for Joan. Fortunately she is well up to all of these challenges. Her heroic character leads her to leap to Joan’s defence in the first place (despite her father’s warning just minutes before that “you cannot champion the cause of every lame dog you meet”. Her determination to do her best for Joan leads her to continue the deception as long as she is able, and her inherent honesty and integrity lead her to confess bravely when the time comes. Finally, her tremendous courage and strength of character enable her to survive two kidnaps, one involving a bang on the head and the other a dose of chloroform and a fall into a canal, arriving back at school quite as chipper as she left it. It seems that her only flaw, and one that is common to many Girls’ Own characters, is impulsiveness and lack of forethought. Pat is a little too perfect for realism, but she is still an appealing character.

The minor characters are equally engaging, occasionally more so. Joan herself (known as Goldie, for her hair) is sweet and clever but rather colourless. Daisy Acland (Dimples), on the other hand, is my personal favourite. Also impulsive and heroic, but much younger, she is instrumental in the apprehending of the criminals and solving of the mystery. She also has an excellent turn of phrase:

“Now J.P. is an English gentlewoman. She knows what’s done.”

”What do you mean, you impudent little creature?” blazed Julie. “English? I’m as English as you are.”

”You may be English,” replied Daisy superbly, “but you are not what I call a gentlewoman.”

Then there is Miss Hammond, who adequately fills the role of Goddess in this particular story – she is beautiful and intelligent; she suspects the identity swap long before anyone else does, and tempers justice with mercy perfectly. The schoolgirl villains, Julie and Molly, are an interesting pair. Julie gets more page time but is, in the end, redeemed by her extreme repentance, whereas Molly tries to push all the blame onto Julie and quietly vanishes. Kate O’Halloran, who seems to be the ringleader of the adult villains, is also nicely portrayed. She is tall and dignified, intelligent and quick-thinking, and it seems that her plan might really have worked if it hadn’t been for the confusion between the two girls. Certainly she creates a very plausible menace throughout the story, and one that is in no way lessened when she appears in person.

The writing is perfectly adequate to the tale and Margaret Griffiths creates a lively, exciting atmosphere and has a delightfully gentle sense of humour. There are a few things that jar strangely, though. She has a slightly irritating habit of putting information in dialogue where it doesn’t quite work – there is a (peculiarly well-spoken) tramp who describes a plot to one of its originators quite unnecessarily. Not to mention the fact that the girls appear not to think it necessary to mention the first attempted kidnapping, nor the fact that they have seen one of Joan’s supposedly disappeared guardians near the school. I can’t help feeling that the whole adventure would have been a lot more realistic but also a lot duller if they had done the proper thing!

This is one of my favourite Girls’ Own stories and I think my love for it comes from the wonderfully portrayed characters. Even the heroine is thoroughly likeable despite her perfection, and the others are quite delightful. I’d recommend this one to anyone who wants a good thrilling read of a book that’s a perfect example of its genre.