I stared down at the frock and thought of dear Mrs. Crapper making it all by hand because she hadn’t got a sewing-machine, and, if the stitches were rather big and uneven, it was only because her eyes weren’t what they had been. I felt I simply couldn’t bear Fiona making fun of it.

I stared down at the frock and thought of dear Mrs. Crapper making it all by hand because she hadn’t got a sewing-machine, and, if the stitches were rather big and uneven, it was only because her eyes weren’t what they had been. I felt I simply couldn’t bear Fiona making fun of it.

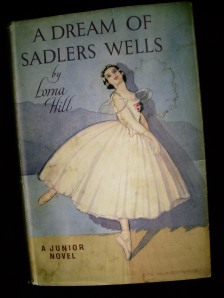

(A Dream of Sadlers Wells)

It’s hard to believe, but Veronica Weston takes the lead in only two of Lorna Hill’s Sadlers Wells books. Impulsive, warm-hearted, intelligent and completely obsessed with ballet, she and her world feel real in a way that few Girls’ Own heroines do. There are many reasons for this – Lorna Hill’s complete mastery of writing in the first person, her sensitive, real and often humorous portrayal of place and atmosphere, her immense skill in creating believable and fascinating characters, and of course Veronica’s own personality, which might be impulsive, illogical and occasionally exasperating but is certainly never dull. As it happens I enjoy ballet books, but I think I would have loved the books about Veronica even if I hadn’t given two hoots about the world of ballet.

In the eleven pages of the first chapter, Lorna Hill paints Veronica’s personality so strongly that it’s as though we have known her for years. Her imagination and sensitivity come instantly to life in her visualisation of the train as an animate being and her warm description of the London she is leaving. Her rather black-and-white view of the world is neatly juxtaposed against Sebastian’s far more liquid one as they discuss smoking on trains:

“Women do smoke nowadays, you know,” said the boy pleasantly. I glanced at him suspiciously, but he didn’t look as though he were being sarcastic. “It was a non-smoker,” I told him severely. He looked at me with raised eyebrows. “I’m afraid you’re what you might call a bit temperamental, my child.”We learn, too, of her interest in the arts and of course her devotion to ballet as she confesses her determination to be a dancer. And at the end of the chapter there is a moment of real vulnerability when Sebastian teases her about her father, unaware that he has recently died. The whole chapter vividly brings to life her open personality, her zest for life and her emotional nature.

To me she will always be the little girl in the cotton frock who danced with bare feet outside my window.

Many Girls’ Own heroines are frightfully honourable, fighting for the honour of their country/school/friend and disdaining anything that smacks of not playing the game. Veronica, refreshingly, doesn’t give such notions the time of day. Indeed, she complains bitterly that the only books her cousins possess are this sort of story, as opposed to “a book about Ballet, or even The Children’s Encyclopedia.” But she does have her own principles; Marcia Rutherford’s studied nastiness not only horrifies her but also takes her by surprise. Even so, it never occurs to her to tell on Marcia, or on any of Fiona’s many unpleasant tricks. And of course, kindness to animals is paramount in importance – not normally given to violence, Veronica pursues and pushes into a pond a youth who gives her favourite monkey a lighted cigarette.

Kindness in general is a strong redeeming feature of Veronica’s. In most books Mrs. Crapper, Veronica’s landlady in London, would either be a figure of fun or make Veronica’s life a misery, but described by Veronica she comes across as a loving, caring person, putting her most precious possessions in Veronica’s room to make her feel at home (even though they are only hideous-sounding gifts from Margate) and sighing sadly over her long-lost husband who ‘went to the dogs’. Arriving in Northumbria, Veronica’s assumption that gates should be opened by herself rather than the chauffeur is met with shocked disapproval by her snobbish Aunt June, although her willingness to help is rewarded months later. As Perkins puts it:

“Well, miss,” said Perkins, wiping his face with a red and white spotted hankie and getting back into the driving-seat, “I sees it this way. When you comes to Bracken, you offers to get out of the car and open the gates for me. That was the very first thing you does. Remember? ‘I’ll do it, Perkins!’ you says. ‘Don’t you bother, Perkins,’ you says. Well, I says to myself that very day – if I can do anything for that youngster, you bet I will!”

Veronica can, when she’s thinking, be sensitive to the feelings of others. There’s a tiny scene in Veronica at the Wells where Veronica, watching Sebastian, suddenly realises how much he minds his cousins living in his ancestral home. She is also, of course, highly sensitive to beauty, especially that of the Northumbrian landscape which she quickly grows to love. Her feelings are often expressed in ballet; she dances Les Sylphides on the grass in her cotton frock as a response to Sebastian’s piano playing, and on another occasion makes a beautiful arabesquein the snow. These sharp emotional reactions can also be less beautiful, and Veronica frequently resorts to shouting, sobbing and foot-stamping. In fact, on the occasion on which Fiona paints faces on the toes of a pair of ballet shoes owned by Madame Wakulski-Viret, Veronica’s old ballet teacher, she shakes Fiona, boxes her ears and has to be dragged off her by Sebastian.

In addition, while Veronica is genuinely caring and can sometimes be sensitive, she’s often quite unperceptive and occasionally selfish. This is probably partly due to her youth – a fourteen-year-old girl today might be quite likely to notice a dawning romance between two of her housemates, but a girl in the 1950s might be less likely to think along those lines, especially someone like Veronica, who seems quite young for her age. By the end of Veronica at the Wells she has matured enough not only to realise that Sebastian will never apologise to her, but to put it aside and understand what his gesture means. She remains, however, completely ineffective in a crisis and almost faints when she briefly thinks she has been thrown out of Sadlers Wells, just as when Stella fainted she merely screamed for help and stood to one side sobbing. It’s not hard to imagine her wringing her hands.

Of course, Veronica’s main motivating force throughout the books is ballet. Undaunted by the lack of facilities at Bracken Hall she practises in the bathroom, using the towel-rail as a barre. Later she plucks up the courage to ask Aunt June for proper ballet lessons and from then on it’s ballet all the way, and we begin to see Veronica’s serious dedication to her art: “Every time you perform is important when you’re a dancer,” she tells Fiona, and it’s a mantra she never fails to live up to. Neither, when Madame Viret turns up at Lady Blantosh’s Garden Fête, does Veronica fail to make the most of the opportunity – within hours Madame Viret has persuaded Aunt June that Veronica should become a professional dancer and arranged an audition for her. This, of course, leads to the dramatic conclusion of the book during which Veronica and Sebastian ride through a night of thick fog so that Veronica can reach the train station in time. Again, in Veronica at the Wells, it never occurs to her to stay and dance in Sebastian’s concert even though he makes it clear that for her to refuse will end the friendship between them – her chance to shine in the world of ballet is of paramount importance.

Of course, that doesn’t mean she isn’t hurt by the rift this causes between herself and Sebastian – she mentions it more than once, and in No Castanets at the Wells, narrated by Caroline, we see letters from Veronica in which, without success, she attempts to heal the divide. In her own book, Veronica at the Wells, she mostly concentrates on her slow, painful progress up the ladder of ballet, her eventual success and, of course, the final reconciliation with Sebastian.

In subsequent books Veronica is frequently mentioned as one of the best dancers of the day, her lyricism much lauded, and often spoken of in the same breath as Margot Fonteyn. She re-emerges briefly in Dress Rehearsal, which features her daughter Vicki as a talented but unenthusiastic dancer and a very different character from Veronica herself – sensible and self-sufficient, though with her mother’s generosity and kindness of heart. In the final chapter we see Veronica finally realise that she has been selfish in expecting Vicki to become a dancer just because her mother is one. Typically of Veronica, once she realises it she has no hesitation in expressing it and in doing everything that Vicki asks her to:

It seems, she thought, that whatever you do, your heart must be in it – whether you are a secretary, a bus-conductor, or selling something in a shop. And especially is this true in some of the more exacting professions – nursing, for instance, music and ballet.

I do regret that Lorna Hill didn’t write more books about Veronica, because for me she’s the most appealing of all the Wells heroines. I like her kindness, her loving nature, her limitless ambition and her imagination, but I also love her impulsiveness and lack of insight. I think most of all I love her almost complete lack of introspection and self-analysis. She’s not the sort of heroine like Joey Bettany, who gets lectured on her responsibilities as a natural leader, or like Darrell Rivers, who is painfully aware of her violent temper and works hard to control it. Instead she pirouettes through life, her blithe assumption that whatever she does she is always acting for the best so convincing that we almost believe it. Above all, she’s entertaining, and that’s what one always needs from a heroine.